Postcolonialism

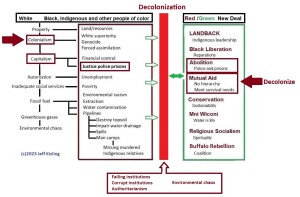

I’m also involved with the Decolonial Repair Network.

(see: Apache Stronghold/Save Oak Flat)

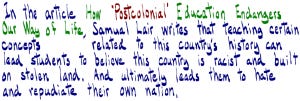

For a revolutionary movement to succeed in any nation, it must convince a critical mass of the people that the existing order is irredeemably evil and must be overthrown. For years, the destructive Left has employed the narrative that “America is systemically racist” to this end. Samuel Lair suggests that the narrative that “America is built on stolen land,” while less often discussed, may be no less essential to the efforts to teach our youth to hate — and, ultimately, repudiate — their own nation.

How “Postcolonial” Education Endangers Our Way of Life

Now that Critical Race Theory (CRT) is being exposed as ahistorical indoctrination, a new permutation of neo-Marxist theory is gaining currency in our schools. It’s called postcolonialism. Its stated mission is to fight “settler colonialism,” a term used to describe any society supposedly built upon the oppression and genocide of indigenous people. Examples of “settler societies” include Israel, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Canada, and the United States.

Starting in the 1990s, the field of settler colonial studies (SCS) brought postcolonial ideology into mainstream academia. Since then, history, anthropology, and sociology departments across the Western world have been teaching college students that their nation is an illegitimate settler colonial society built upon white supremacy, theft, and genocide perpetrated against indigenous peoples.

How “Postcolonial” Education Endangers Our Way of Life by Samuel Lair, tomklingenstein.com, February 4, 2025

I do believe our nation is a settler colonial society built upon white supremacy, theft, and genocide perpetrated against indigenous peoples. Others can disagree that we are a settler colonial society. They may question white supremacy, land theft, and/or genocide against indigenous peoples.

And I do not believe that teaching these things will “lead our youth to hate — and, ultimately, repudiate — their own nation” as it says in the editor’s note above. An important part of education is to teach students how to evaluate the many factors involved in a given piece of history by developing critical thinking skills.

These opposing views cannot both be correct.

It comes down to a question of beliefs and values. You either believe colonial powers have the right to conquer other peoples and their lands, or you do not. Much of written history is an ongoing story of conquest.

Not as widely told are the daily acts of community and faith that occur during those same times.

As a spiritual person, a Quaker, my life is an attempt to discern what the Spirit is asking of me and then try to do that. I seek to understand what is going on around me. Try to determine what is right, what is wrong. Currently, and in the past.

Life experiences also inform my understanding, which is why I have sought out, and have been led by the Spirit to connect with those who have experienced and are continuing to experience injustice today. I have witnessed the impacts of injustices, past and present, on indigenous communities, and those of people of color.

Those who, like Lair, want to minimize the consequences of colonialism of this country don’t seem to know the historical traumas of the past don’t end there. That trauma is passed from generation to generation. Those living today are dealing with that history, and in many cases the ongoing oppression.

This is part of the reason why it is crucial to teach an all-encompassing history today. Both for those oppressed, and to help those who haven’t had those experiences understand this oppression. By all-encompassing I mean telling the stories of all of those involved in a given period of history. Still, the teacher’s views and curriculum standards shape how history is told.

Oregon’s 8th-grade history standards ask students “to examine the differing forms of oppression, including cultural and physical genocide, faced by Indigenous Tribes and acts of resilience and resistance used by Indigenous peoples in response to settler colonialism.”

Among the most powerful exponents of postcolonial ideology in K-12 curricula is the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS), the nation’s largest social studies organization. In 2018, NCSS issued a policy statement declaring that because “all education in the United States takes place on Indigenous lands,” social studies education ought to prioritize “Indigenous perspectives” and challenge “dominant narratives and Eurocentric logics in curricula.”

Of course, our national story is deeply intertwined with the history of American Indians. Any rigorous set of standards would include relevant discussions of them when appropriate. However, when “indigenous perspectives” are made the dominant framework in order to “decolonize” the curriculum, presentations of significant historical figures and events are either distorted or entirely omitted to make way for niche topics. Oregon’s 5th-grade history standards covering colonial and early U.S. history excludes mention of Christopher Columbus in favor of analyzing “the distinct way of knowing and living amongst the different Indigenous peoples of North America before contact.”

How “Postcolonial” Education Endangers Our Way of Life by Samuel Lair, tomklingenstein.com, February 4, 2025

The exclusion and distortion of traditional American history in favor of “indigenous perspectives” is both ideologically and politically motivated. The central tenet of postcolonial ideology is that the perceived injustices of the past are not isolated to a limited set of finite historical moments. The Australian historian Patrick Wolfe, considered one of the founding scholars of SCS, explains that “Invasion is a structure not an event,” meaning that all settler colonial societies perpetuate the oppression and genocide of indigenous peoples by virtue of their existence.

Accordingly, the goal of postcolonial ideology extends far beyond simply including nontraditional perspectives in K-12 curriculum; its aim is to indoctrinate and train a generation of radical Left activists. As explained by NCSS, “social studies education has a responsibility to oppose colonialism and systemic racism,” making it essential for teachers to understand “their role as agents for social change.”

How “Postcolonial” Education Endangers Our Way of Life by Samuel Lair, tomklingenstein.com, February 4, 2025

I’m of the firm opinion that a system that was built by stolen bodies on stolen land for the benefit of a few is a system that is not repairable. It is operating as designed, and small changes (which are the result of huge efforts) to lessen the blow on those it was not designed for are merely half measures that can’t ever fully succeed.

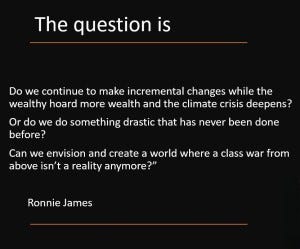

So the question is now, where do we go from here? Do we continue to make incremental changes while the wealthy hoard more wealth and the climate crisis deepens, or do we do something drastic that has never been done before? Can we envision and create a world where a class war from above isn’t a reality anymore?”

Ronnie James, Indigenous organizer

postcolonialism, the historical period or state of affairs representing the aftermath of Western colonialism; the term can also be used to describe the concurrent project to reclaim and rethink the history and agency of people subordinated under various forms of imperialism. Postcolonialism signals a possible future of overcoming colonialism, yet new forms of domination or subordination can come in the wake of such changes, including new forms of global empire.

Postcolonialism should not be confused with the claim that the world we live in now is actually devoid of colonialism.

Postcolonialism (also post-colonial theory) is the critical academic study of the cultural, political and economic consequences of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on the impact of human control and exploitation of colonized people and their lands. The field started to emerge in the 1960s, as scholars from previously colonized countries began publishing on the lingering effects of colonialism, developing a critical theory analysis of the history, culture, literature, and discourse of (usually European) imperial power.

Postcolonial, as in the postcolonial condition, is to be understood, as Mahmood Mamdani puts it, as a reversal of colonialism but not as superseding it.[1]

Inclusive Social Science: Expanding the Narrative

Throughout the K-12 standards, students investigate how gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, religion, class, and disability often shape laws, policies, and other social interactions.

Teachers should include culturally relevant examples of the histories, contributions, and perspectives of traditionally underrepresented individuals and groups, including individuals who are American Indian/Alaska Native/Native Hawaiian, Americans of African, Asian, Pacific Island, Chicano, Latino, Middle Eastern or Jewish descent, immigrants, or refugees, of various religious identities, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other traditionally underrepresented groups.

2024 Oregon Social Science Standards, Oregon Department of Education, June 7, 2024

Given that all education in the United States takes place on Indigenous lands, National Council for the Social Studies recognizes the responsibility of social studies education to respect and affirm Indigenous peoples, nations, and sovereignty. NCSS supports the creation and implementation of social studies curricula that explicitly present and emphasize accurate narratives of the lives, experiences, and histories of Indigenous Peoples, their sovereign Nations, and their interactions—past, present, and future—with Euro-American settlers and the government of the United States of America. NCSS further supports communities, teachers, teacher educators, curriculum writers, district administrators, departments of education, and Tribal Education Departments/Agencies (TEDs/TEAs) working to provide more accurate learning opportunities for students at all grade levels

that emphasize the sovereignty and self-determination of Indigenous Peoples and Nations, past, present, and future.

Toward Responsibility: Social Studies Education that Respects and Affirms Indigenous Peoples and Nations. A Position Statement of National Council for the Social Studies. Approved March 2018